Lichenizing Pedagogy

Art Explorations in More-than-Human Performance and Practice

Published 14 October 2024 in Articles

24 mins read

Keywords

lichenizing, pedagogy, multispecies learning, ecoculture, art, education

Authored by

Rachel Zollinger, University of Arizona

rzollinger@email.arizona.edu

Mariko Oyama Thomas, Independent Scholar, Taos, NM

mariko.o.thomas@gmail.com

Hollis Moore, University of New Mexico

hollismoore@gmail.com

Kaitlin Bryson, Artist, Santa Fe, NM

kaitbryson@gmail.com

Published in

Research in Art & Education, Vol. 1, 2022, p. 23-33

Thematic Issue: On animals, plants, bryophytes, lichen, and fungi in contemporary art and research.

Published May 27, 2022

DOI

Abstract

This project of performative writing and visual inquiry proposes the concept of “lichenizing” as a collaborative methodology for engaging with the lively pedagogy of the more-than-human. Looking to the multispecies mosaic of Lichen as teacher and ally, this arts-based, collectively produced foray considers transcorporeal, intermingled relationships as a pedagogical tool for fostering a radical, ecologically-centered curiosity for learning and making. To support our theorizing, we present two collaborative art projects where tenets of lichenizing were utilized to instruct process and form, and suggest further exploration and research on the practice of “lichenizing.”

Introduction

[1] We use the term queendom as a small symbolic way to subvert the patriarchal roots of taxonomic systems.

[2] We use the term composted to consider the decomposition of our words into one another’s until the product is fertile.

[3] Here we refer to Haraway’s (2016) developing of Dempster’s (2000) concept of “collectively-producing systems that do not have self-defined spatial or temporal boundaries” (p. 33).

[4] Here we rely heavily on Alaimo’s (2010) explanation of transcorporeal which understands all em-bodied beings as intermeshed with the material world and affected and effected by it.

[5] We take up Bennett’s (2010) reasoning that to counter the narcissism of humans in charge of the world, we need to cultivate some anthropomorphism for catalyzing sensitivity to nonhuman agency.

When we first learned of Lichen, or rather how to see Lichen, in our own places, during separate times of our independent lives—each of us had confused and entranced experiences. As desert dwellers we had often encountered them hugging the basalt embedded in sandstone hillsides, these mysterious amalgamations of green and ochre and silvery grey that turned iridescent after rain. It took many years to realize their biological significance, which perhaps is the magic of an organism that has worked so long to make the planet what we know it to be. As academics, artists, and community scientists, all the authors of this paper have long been disenchanted with the anthropocentrism and overt individualism we had experienced in much of our pedagogical lives, both as students and teachers, and considering Lichen more closely seemed to miraculously address these concerns simply by existing. In the context of Western/ized science, Lichens are full of riddles. In their transcendence of taxonomic boundaries, most laypeople awkwardly and incorrectly relegate them to the plant queendom. [1] Googling the word “lichen” gives an equally myopic understanding; the first definition found describes them as “a simple, slow-growing plant that typically forms a low crust, leaflike, or branching growth on rocks, walls, and trees” (Oxford Languages, n.d.). However, Lichens are anything but simple and not necessarily plants. Lichens are complex formations of at least one fungus variety with an alga or cyanobacterium—sometimes both. This allows Lichens to use photosynthesis (which fungi lack) while still being heterotrophic, meaning absorbing nutrients through their bodies (which plants lack) (Tripathi & Joshi, 2019). The sheer possibilities of their multiplicities in form(s) promote critical inquiry of the nature of personhood, working relationships, and collaboration. This mutually-obligate relationship between plant, bacteria, and fungus spurred our collective to think more critically about the way that arts and academia might symbolically emulate Lichens in how we learn, teach, and co-create.

The following sections of this experimental essay start by briefly framing the problems we have experienced with traditional pedagogies and the urgency we feel in investigating collective working methods. Next, we introduce Lichen as a teacher and an ally, and offer the term “lichenizing” as a way to frame our desired emulation of Lichen collaboration and illuminate the connective relations that enable knowledge to ebb and flow between living entities. Finally, we turn to two arts-based projects exploring how we could employ lichenizing as a strategic process for collaborative learning and making. The first project we present uses an experimental performative writing style that imbricates our voices into a textual and visual tapestry. This was a deliberate move to blur the boundaries between ourselves as individuals and ourselves as a collective. It is composed of several scores (or instructions for performance) that we collectively combined, morphed and ‘composted’ [2] into a singular piece of writing through several remote meetings, then individually performed. The process was meant to blur individualism in the process and was a reflection of sympoiesis [3] and transcorporeality [4] in motion. The second project is a physically built earth wall that we constructed in Michoacán, Mexico. Over several days we shaped a short, walllike sculpture as a symbolic transitory space between two biological zones: one semi-arid, sun-drenched, and inhabited by gigantic prickly pear cacti; the other lush and densely vegetated with water-loving plants. The act of co-building in the transition space was a reflection on weathering and dwelling—two ways of being we associated with the evolutions and lithic longevity of Lichens on this Earth. Together, the two projects served as practices in lichenizing, and successful forays into intensive ways of collaboration. [5] While the first project showed how we could meaningfully collaborate and embody the ethics we associate with Lichen through an online format, despite pandemic and locational restrictions, the second project employed an earthly approach that conceded to the materiality of place. We find that both approaches may be necessary in future lichenizing movements.

Considering Lichen

Consider Lichen. Easily overlooked, or mistaken for moss or simply colorful rock, Lichens are unsung marvels of this world. Scabbing over stone, curling out in brittle leaves, or bristling like tiny shrubs, the many forms of Lichens flourish over otherwise inhospitable cliff faces and walls, cling to the bark of the oldest trees, and hold together soil in crusts. Some even blow about freely in the wind, untethered to any substrate. Their humble appearance belies their intricate biology and ecological importance. Lichens are dwelling places (Sheldrake, 2020), knitting sanctuary and home for myriad organisms out of mere rock, sunlight, and air. Lichen’s thallus is a tiny ecosystem composed of distinct partners, a photobiont (plant) and at least one mycobiont (fungus), coalescing into an imbricated, interwoven structure of fungal filaments and alga/cyanobacteria cells. However, Lichen’s emergent whole is certainly not merely a few fungi and photosynthetic algae. Hundreds, if not thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, of other species of bacteria and fungi dwell within the thallus in a world of complex interactions, some beneficial, some antagonistic (Pringle, 2017; Tripathi & Joshi, 2019). They are veritable oddkin of worlding (Haraway, 2016). Lichens’ penchant for inhabiting seemingly inhospitable spaces make worlds possible. During their lives and deaths, they are leaders of soil formation, a living geological force (Sheldrake, 2020) capable of transforming barren spaces of recent upheaval—volcanic eruptions, receding glaciers, landslides—to burgeoning landscapes (Tripathi & Joshi, 2019). They ‘weather’ rock surfaces, first by their growth patterns and then by very slowly dissolving and digesting it with powerful acids. This extraordinary process does more than break down rock; it unlocks the minerals necessary for the metabolic cycles of life (Sheldrake, 2020). When Lichens die and decompose, their nutrient-rich thalli contribute biomass to new soils and new ecosystems (Tripathi & Joshi, 2019). The lichenized kinship formed between members of distinct biological queendoms is sympoiesis, described by Dempster (2000) as “complex, self-organizing but collectively producing, boundaryless systems” (p. 1). Sympoietic systems are adaptive and emergent. Lichen’s collective physiology is distinctly unique from their discrete organisms’ bodies, resembling none of the synthetic partners (Tripathi & Joshi, 2019). Like most things, they are irreducible to their parts, but Lichen’s transmutations through sympoiesis exceed the complexity of more than the sum of their parts. Lichens are other than the sum of their parts (Gowan, 2008). Lichenized species are enmeshed with(in) each other: living-with, making-with, and dying-with. This is transcorporeality, coined by Alaimo (2010) as an alternative to dematerialized epistemologies that ignore the “fleshy beings with their own needs, claims, and actions” (p. 2) who inter/intra-act in the world in very real, very material ways. Transcorporeality “reveals the interchanges and interconnections between various bodily natures” (p. 2), a vital togetherness that pulses through all our bodies. Microbiologist Lynn Margulis, and then others, helped us realize that we humans are not so alone in our own bodies, anyway, with 90% of our cells owing their genomes to bacteria (Hird, 2012), to say nothing of the fungi, viruses, and protists living, developing, and evolving with us (Gilbert et al., 2012). Lichen’s multispecies symbiosis is not exclusive, or even uncommon to life; in fact, only bacteria themselves are able to exist in species singularity. Life owes its evolution to the intimacy of strangers (Margulis, 1981). As Haraway (2016) summed up, “we always become-with each other or not at all” (p. 4).

Problematizing Western/ized Pedagogies in the Anthropocene

[6] We agree with Tsing (2010) that practicing the art of noticing helps one listen and pay attention to lively worlds above, surrounding, beneath, and within us.

[7] We use this term as a more inclusive description of who performs science, regardless of education, background or status.

We were most interested in experimenting with the processes of Lichen and these projects as a precursor to building a less anthropocentric pedagogy. As an arts collective, we commonly employ acts of noticing [6] as a methodology that might (re)train ourselves to think, and thereby act, in ways deliberately attentive to the beings and ecologies we engage with every day. Simultaneously, we have come to realize many pedagogical practices in the Western tradition direct our attentions to individualistic and anthropocentric thinking. These are norms that we vehemently argue cannot continue, and adopting Lichen as inspiration and teacher is a fecund rebellion against the destructive humanism we perceive traditional pedagogies to promote. In recent years, many scholars, activists, artists, and community scientists [7] have challenged what is considered knowledge in academia (Agarwal & Sengupta-Irving, 2019; Bang et al., 2014; Kaishian & Hasmik, 2020; Kimmerer, 2002; Styres, 2018). Notions of “public pedagogy” have expanded education as multidimensional consciousness, resistance, and lived practices of everyday life (Sandlin, et al, 2011), while others have suggested we expand our understandings of educational spaces and processes, suggesting that we learn best within an ecology of relationships and shared experiences (Burdick et al., 2014; Falk & Dierking, 2013; Luke, 2009). Therefore, we insist, the relationship between pedagogy and the more-than-human should be involved. Scholars in multiple fields have questioned Western/ized empirical thought and and how this practice works to contrive some voices and ways of knowing as illegitimate. For example, the adoption of phenomenological thinking works to challenge objective experience (see Langsdorf, 1994; Kinsella, 2007; Martinez, 2000). Additionally, Indigenous and Traditional Ecological Knowledges (TEK) that tend to privilege the more-than-human have been more present in assigned coursework and references (Cajete, 2020; Kimmerer, 2002), but in our experiences are often relegated to a singular unit in a course, serving more as a nod to diversity and inclusion rather than the real thing, reinstating its marginalization. Indigenous epistemologies have long offered views alternative to utilitarian, inert nature (Berkes, 2018/1999) but for many raised in Western traditions, dismantling hierarchies of being and knowing conflicts with the epistemologies and ontologies in how we live and work. Members and institutions of dominant Western/ized cultures think, act, make policy, and create structures as if the endeavors of learning and teaching are solely human undertakings. This results in anthropocentric educational productions within our schools, institutions, and broader society. Humans have historically been insecure about what makes us different from other beings, repeatedly searching for some ability or capacity that sets us apart from the rest, resulting in Western traditions both anciently and presently exercising human superiority and highlighting human-only intelligence in educational systems. For example, Slack and Whitt (1990) have noted that much of critical theory and the basis of cultural studies is definingly anthropocentric, which means much work encompassing social change is as well. We argue that it is crucial that humans (pedagogues and academics included) act as though we are unquestionably connected to the morethan-human world in explicit and implicit ways, and abstaining from this is dangerous for our species and our planet. Despite living with(in) the Anthropocene, a human-induced epoch heralded by land, water, and air degradation, plummeting biodiversity, species extinction, and climate change, pedagogy has remained an almost completely humanist field (Graham, 2007; Snaza et al., 2014), despite the endless positive possibilities of expanding to include more-than-humans.

Lichenizing Pedagogy

[8] Here we mean “weathering” in the sense of Lichens as a living geological force capable of wearing down rock and other substrates, distinct from Neimanis & Walker’s (2014) concept of “weathering” as the relationship between human bodies and climate.

How can those studying and working in educative capacities make this process into a more-than-human endeavor? And what role might art have to play in this as far as experimentation, emulation, and exploration? What follows is an attempt use art, collaboration, and play to involve what we perceive to be more-than-human inspired processes in our work. In this exploration, we adopt Lichen as our teacher, whose processes of being inspire us to offer sympoietic performative gestures for (re)learning interconnectedness. Life does not exist in singularity, and neither should our learning. We argue that Lichens provide an excellent example on re-animating pedagogy and de-centering Western human norms of teaching and learning. Lichens show us we have an opportunity to interweave and imbricate learning and teaching within the animacy and agency of other more-than-human beings and avoid the “species-wide solipsism” (Hawkins, 1998, p. 174) that has brought the world to a precarious tipping point, from climate to social catastrophe. Pedagogy is a crucial frame to look at more-than-human relationships with humans, and power in general, as study of the field asks who educates whom, and to what aim. In questioning what humans might not know, we can decenter our narrow authority as human teachers, and turn instead to our myriad oddkin to learn. To lichenize pedagogy means weathering [8] the seemingly immutable practices that govern how we teach and who we revere as teachers, slowly but intentionally dissolving the fallacies of ignoring our interconnected realities. We must question and (un)learn what it means to be individual or in any kind of hierarchy, and to make new or simply forgotten relations of reverence with our earthly co-habitants. This requires interrogation of the ill-informed assumptions we make about the intelligences of other lifeforms, the apathy we show for their embodied creativity, the ignorance of their world-making wisdom. We must establish dwelling places, literally and figuratively, where we may explore interspecies pedagogy through multidisciplinary inquiry and experimentation. Pedagogy is a collective endeavor of techniques, processes, and worldviews, operating across disciplines, processes, and intelligences—an active sympoiesis that we argue should be understood across species as well. Pedagogy is neither static nor didactic; it is living and interactive knowledge (Tochy & Munby, 1993). Considering pedagogy as a transcorporeal practice flowing through actions and meanings across myriad, multispecies bodies—transforming and transmuting them in emergent ways made only possible by their collaboration, encourages rethinking education not as a human endeavor but as a shared project by the whole of the Earth.

Lichenizing in Practice: Two Performative Acts

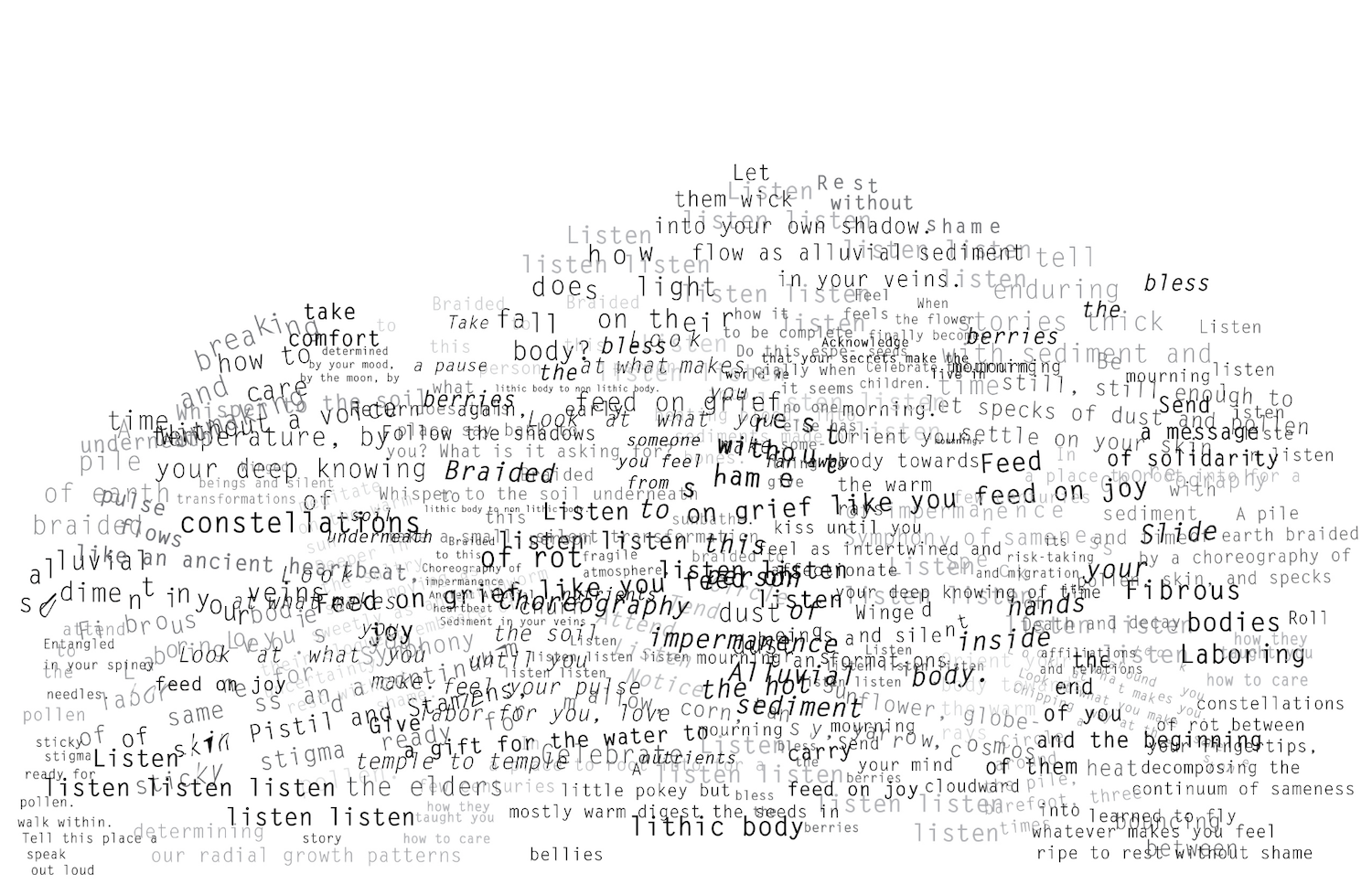

Below, we present two projects of art research that lean into a lichenized methodology. As scholars and pedagogues, we are often in the privileged position of instructing others, leading workshops, and teaching classes. In our continued efforts to bridge theory to practice, we eagerly positioned ourselves as curious (un)learners, keen to evolve our consciousness and transform our habits of being. We chose to engage in art-based endeavors, believing that, as Greene (2007) suggests, “of all the human creations, works of art are most likely to resist fixed boundaries” (p. 660). We were guided by four habits of Lichen that we have observed: weathering and dwelling, and sympoiesis and transcorporeality. We use an experimental performative writing style to present our projects. The style seeks to imbricate our voices into a tapestry that, like Lichen, blurs the boundaries between ourselves as individuals and ourselves as a collective. This discursive practice serves both as the labor of rhetorical performance and as sense-making of our visual inquiries. We agree with Pomarico (2016) that language, similar to pedagogy, shares a paradox that “reiterates a vertical, authoritarian experience, and, at the same time, offers the possibility of emancipation, freedom, and justice” (p. 209). We believe language, and its textual partner writing, are not static forms but organic, dynamic processes with the capacity for provoking discovery, and sometimes recovery, of relationships we did not know or forgot we had. Writing made to perform is “embodied, creative counter-speech” (Pollock, 1998, p. 74) that tests and practices language in evocative, radical propositions, and calls forth action. As a sense-making process, we experience performative writing as a way of becoming conscious of the medium, of considering the weight and materiality words carry in ourselves, and the living world. Words “do not live alone or in the mind” (Zapata et al., 2018, p. 492), they become world-makers. We understand performative words to operate between consequential meaning and rhetorical aesthetic; to contain a potent magic of potential action and response; to project alternative modes of thinking and being through reinterpretation of meaning and possibility. The first project is an experimental performance of sympoiesis and transcorporeality imagined through language and experience as a ‘score.’ Scores recall the experimental art performances of the Fluxus Movement, which took inspiration from musical notation for the performer to understand which direction to take, and aimed to subvert and conflate notions of performer and audience (Friedman et al., 2002). To write the score, we tossed our previous score-based writings exploring the role of noticing and relationships to place into a textual ‘compost pile’ of sorts, then collectively sifted through the rich decomposition for fertile words and phrases (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Textual compost pile of existing scores

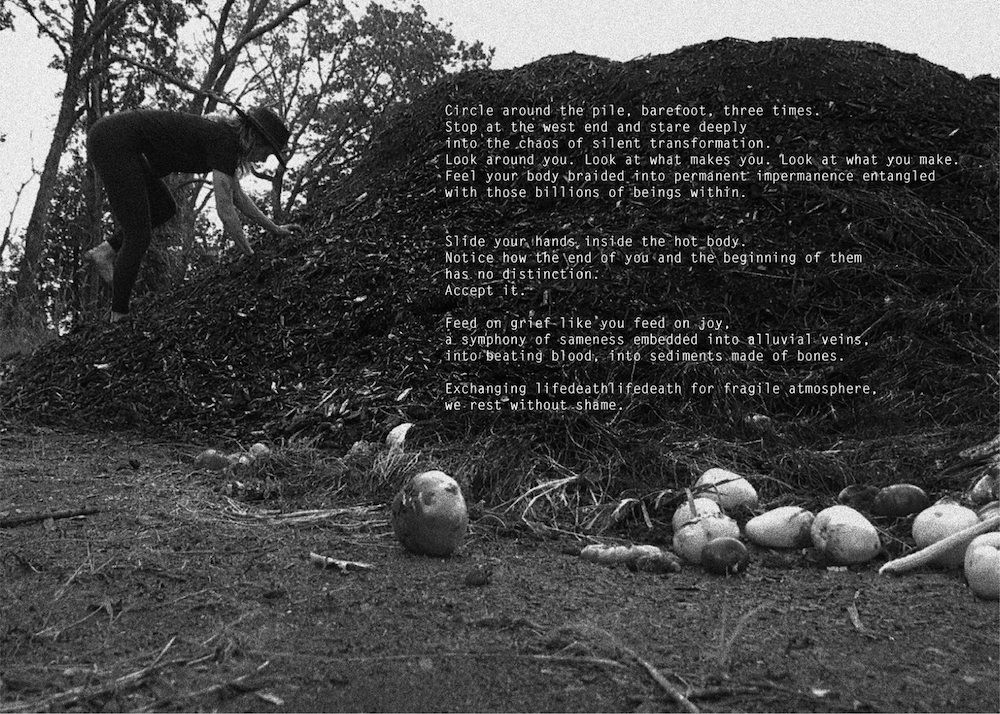

We watched as words, randomly pasted into a shared Google document in a seemingly amorphous jumble, sprouted as new interactions, new meanings, new potentials previously unthought, through their serendipitous rearrangement. We noticed how a few words surfaced again and again, echoing our desires to listen more deeply to the vitality surrounding us. We threaded these bits of language and emergent poetry together into a proposition or actionable instructions—a score. Scores are only partially made by writing; they become something else by another’s interpretation and enactment. Our next step was to perform these scores within the multispecies enmeshment of our body(ies), community(ies), and place(s). Visual documentation served as the final step in this process (see Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 2. Collaborative, emergent score and performance

Figure 3. Score performances with compost

The second project is a materially focused meditation on dwelling and weathering though paid close attention to the intricacies of co-making and co-habitation. We were interested in how these particular words could (re)inhabit meaning as physical processes in materials, bodies, and place, and instruct us on how we might think through the experience of collaborative making. We constructed a small wall to serve as a visual marker between ecological transition zones, considering the porous and blended nature of border areas between bioregions as something already so familiar to Lichens (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Rock and adobe wall construction

Using native volcanic rock and scavenged century-old adobe and ceramic roof tiles, we took design cues from the spaces we noticed Lichens already residing: the local vernacular architecture, the drystack walls encircling pasture and cropland, the amalgam of geologic formations in the hills surrounding us. Taking pause in our labors, we greeted the others—insects, spiders, lizardswho had swiftly joined us in the endeavor of making place. Later, we carried the process of weathering through our reflective writings on these notions, eroding whole sentences and rearranging the textual landscapes (see Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 5. Reflection on dwelling and weathered text

Figure 6. Reflection on weathering and weathered text

Conclusion: Fertile Dust

In our explorations of lichenizing, we noticed how the tendrils of each other’s words and gestures laced through one another’s, vitally linking our creativity. We traced ideas outside of our human bodies, felt our own consciousness reach toward the deep and diverse knowledges already welled up in the places we found ourselves. We gave ourselves over to process, delighting in the unmaking and making of possibilities, content knowing that the dust of our labors would settle into burgeoning landscapes of knowledge. We maintain that this is not the final version of this idea, whether it is consecrated in the perceived permanence of the publishing process, as sculpture, or as photo-documentation, as in order to behave like Lichen, we need to be accepting of the constant evolutions of all things, and the (very) long time that it takes to make and unmake a world into existence. Lichens live in lithic time; they are slow, transformative processes with vast, abounding implications. Using “nature” as a teacher allows us to integrate ourselves in the processual aspects of learning and making, and how that affects our identities. While we are fully aware of the ironies of using a human language to talk about a non-human entity, whose concept of language scientists have only the faintest idea about, we still find it important to practice including more than-human methods in human practices, as the one of the first steps to decentralizing humans is to start considering, at a very base level, that humans have something to learn from other species. We are not suggesting anthropomorphism, so much as borrowing a perceived process from another species and adopting in terms that humans can use, while finding openings and overlaps where our ways of being and knowing knit together. We are inspired by multispecies anthropologist Tsing’s (2014) suggestion that “[o]ur humanness is also a starting point, an opening for getting involved in multispecies worlds” (p. 34). We learn by observing, participating, and doing as others do. It matters, then, who our models for thinking and being are. Lichen, as teacher and ally, offers us ways of radical imagining, then learning, then being.

References

Agarwal, P. & Sengupta-Irving, T. (2019). Integrating power to advance the study of connective and productive disciplinary engagement in mathematics and science. Cognition and Instruction, 37(3), 349–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2019.16 24544

Alaimo, S. (2010). Bodily natures. Science, environment, and the material self. Indiana University Press.

Bang, M., Curley, L., Kessel, A., Marin, A., Suzukovich, S., & Strack, G. (2014). Muskrat theories, tobacco in the streets, and living Chicago as Indigenous land. Environmental Education Research, 20(1), 37-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2 013.865113

Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter. A political ecology of things. Duke University Press.

Berkes, F. (2018). Sacred ecology (4th ed.). Routledge. (Original work published 1999)

Burdick, J., Sandlin, J. A., & O’Malley, M. P. (2013). Problematizing Public Pedagogy. Routledge.

Cajete, G. A. (2020). On science, culture, and curriculum: Enhancing native american participation in science-related fields. Tribal College: Journal of American Indian Higher Education, 31(3), 40-44.

Demster, B. (2000). Sympoietic and autopoietic systems: a new distinction for self-organizing systems. In J. K. Allen & J. Wilby (Eds.), Proceedings of the World Congress of the Systems Sciences and ISSS 2000 (pp. 1-15).

Falk, J. & Dierking, L. (2013). The museum experience revisited. Left Coast Press.

Friedman, K., Smith, O., & Sawchyn, L. (Eds.). (2002). Fluxus performance workbook. Performance research e-publication. Retrieved from https://www.thing. net/~grist/ld/fluxusworkbook.pdf

Gilbert, S., Sapp, J., & Tauber, A. (2012). A symbiotic view of life: we have never been individuals. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 87(4), 325-341.

Goward, T. (2008). Twelve readings on the lichen: the face in the mirror.Evansia, 25(2), 23-25.

Graham, M. (2007). Art, ecology and art education: locating art education in a critical place-based pedagogy. Studies in Art Education, 48(4), 375-391. https://doi. org/10.1080/00393541.2007.11650115

Haraway, D. (2016). Staying with the trouble. Duke University Press. Hawkins, R. Z. (1998). Ecofeminism and nonhumans: continuity, difference, dualism, and domination. Hypatia, 13(1), 158-197.

Hird, M. (2012). Animal, all too animal: blood music and an ethic of vulnerability. In A. Gross & A. Vallely (Eds.), Animals and the human imagination (pp. 331-348). Columbia University.

Kaishian, P. & Djoulakian, H. (2020). The science underground: mycology as a queer discipline. Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience, 6(2), 1-26. http:// doi.org/10.28968/cftt.v6i2.33523

Kimmerer, R. W. (2002). Weaving traditional ecological knowledge into biological education: a call to action. Bioscience, 52(5), 432–438.

Kinsella, W. J. (2007). Heidegger and being at the Hanford reservation: Standing reserve, enframing, and environmental communication theory. Environmental Communication, 1(2), 194-217.

Langsdorf, L. (1994). Why phenomenology in communication research? Human Studies, 17(1), 1-8.

Luke, C. (2009). Feminisms and pedagogy of everyday life. In J. Burdick, J. Sandlin, & B. Schultz (Eds.), Handbook of Public Pedagogy: Education and Learning Beyond Schooling (pp. 130-138). Routledge.

Margulis, L. (1981). Symbiosis in cell evolution: Life and its environment on the early Earth. W. H. Freeman.

Martinez, J. M. (2000). Phenomenology of Chicana experience and identity: Communication and transformation in praxis. Rowman & Littlefield.

Murphy, P. (2008). Defining pedagogy. In K. Hall, P. Murphy & J. Soler (Eds.), Pedagogy and practice: Culture and identities (pp. 28-39). The Open University and Sage.

Neimanis, A. & Loewen, R. (2014). “Weathering”: climate change and the “thick time” transcorporeality. Hypatia, 29(3), 558-575.

Pollock, D. (1998). Performing writing. In P. Phelan & J. Lane (Eds.), The ends of performance (pp. 73-103). New York UP.

Pomarico, A. (2016). Situating us. In A. P. Pais & C. Strauss (Eds.), Slow reader (pp. 207224). Astrid Vorstermans.

Pringle, A. (2017). Establishing new worlds. In A. Tsing, H. Swanson, E. Gan & N. Bubandt (Eds.), Arts of living on a damaged planet (pp. 157-167). University of Minnesota Press.

Oxford Languages (n.d.). Lichen. In Oxford Languages dictionary. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://www.google.com/ search?q=lichen+definition

Sandlin, J. A., O’Malley, M. P., & Burdick, J. (2011). Mapping the complexity of public pedagogy scholarship: 1894-2010. Review of Educational Research, 81(3) 338-375. http://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311413395

Schubert, W. H. (2010). Outside Curricula and Public Pedagogy. In J. Burdick, J. Sandlin & B. Schultz (Eds.), Handbook of Public Pedagogy (pp. 38-47). Routledge.

Sheldrake, M. (2020). Entangled life: How fungi make our worlds, change our minds & shape our futures. Random House.

Slack, J. D. & Whitt, L. A. (1992). Ethics and cultural studies. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson & P. Treichler (Eds.), Cultural studies (pp. 571-592). Routledge.

Snaza, N., Applebaum, P., Bayne, S., Carlson, D., Morris, M., Rotas, N, Sandlin, J., Wallin, J., Weaver, J. (2014). Toward a posthuman education. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 30(1), 39-55.

Styres, S. (2018). Literacies of land: decolonizing narratives, storying, and literature. In L. T. Smith, E. Tuck & K. W. Yang (Eds.), Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: Mapping the long view (pp. 24-37). Routledge.

Tochon, F. & Munby, H. (1993). Novice and expert teachers’ time epistemology: A wave function from didactics to pedagogy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 9(2), 205–218.

Tripathi, M. & Joshi, Y. (2019). Endolichenic Fungi: Present and Future Trends. Springer.

Tsing, A. (2010). Arts of inclusion, or how to love a mushroom. Mānoa, 22(2), 191-203.

Tsing, A. (2014). More-than-human sociality: a call for critical description. In K. Hastrup (Ed.), Anthropology and nature (pp. 3752). Routledge.

Zapata, A., Kuby, C., & Thiel, J. (2018). Encounters with writing: becoming-with posthumanist ethics. Journal of Literacy Research, 50(4), 478-501. http://doi. org/10.1177/1086296X18803707