Education for Sustainability

Understanding Processes of Change across Individual, Collective, and System Level

Published 14 October 2024 in Articles

Detail from a drawing by art educator Victoria Pavlou during the workshop 'A Meeting of Worlds: Where the Weeds Grow Tall', Nicosia, April 2023

30 mins read

Keywords

inner transition, sustainability, subjectivity, education for sustainability, transformative education, embodied knowledge, micro-phenomenology

Authored by

Elin Pöllänen & Walter Osika (1, 2)

Eva Bojner Horwitz (1, 2, 3)

Christine Wamsler (4)

(1) Center for Social Sustainability, Department of Neurobiology, Care Science and Society, Karolinska Institute, 17177 Stockholm, Sweden

(2) Centre for Psychiatry Research, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet & Stockholm Health Care Services, 17177 Stockholm, Sweden

(3) Department of Music, Pedagogy and Society, Royal College of Music, 11591 Stockholm, Sweden

(4) Centre for Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS), Lund University, 22100 Lund, Sweden.

Correspondence

christine.wamsler@lucsus.lu.se

Academic Editor

Susan Prescott

Published by

Challenges, Volume 14, Issue 5

DOI

Researchers and practitioners increasingly emphasise the need to complement dominant external, technological approaches with an internal focus to support transformation toward sustainability. However, knowledge on how this internal human dimension can support transformation across individual, collective, and systems levels is limited. Our study addresses this gap. We examined the narratives of participants in the sustainability course “One Year in Transition”, using micro-phenomenology and thematic analysis. Our results shed light on the dynamics of inner–outer change and action and the necessary capacities to support them. This related to changes regarding participants’ perspectives, which became more relational and interconnected. We also showed that participants increasingly seek an inner space that provides direction and freedom to act. The data suggested that this, over time, leads to increasing internalisation, and the embodiment of a personal identity as a courageous and principled change agent for sustainability. Our results complement extant quantitative research in the field by offering a nuanced picture of the entangled nature of inner–outer transformation processes and associated influencing factors. In addition, they point towards ways in which inner dimensions can be leveraged to achieve change, thus filling existing knowledge gaps for reaching sustainability and associated goals across all levels.

Introduction

The issue of climate change is posing an increasing challenge to sustainable development worldwide [1–4]. Our current policy approaches have not been able to address the magnitude and rate of change that is needed, and it is increasingly clear that sustainability goals and targets that have been established at international and national levels will not be reached [2,5]). Sweden is no exception to this, even though the country is often declared a forerunner in climate governance.

The way in which climate change and related approaches have been framed in Sweden, and worldwide, has been closely related to the biophysical discourse in which climate change has mainly been seen as an external technical challenge [6] (In this article, external and internal are used synonymously as outer and inner. Transformation and change are used interchangeably and relate to the same idea of a fundamental change in a system (see Ref. [7]). Consequently, much focus has, so far, been placed on solutions that address external socio-economic structures and technology [8]. It is, however, becoming increasingly clear that such approaches alone will not meet the 1.5–2° C climate mitigation target, because the current mechanistic stance is not tackling the root causes of the problem.

Scholars and practitioners are thus increasingly emphasising the need to complement the current external perspective with an internal focus identifying individual and collective beliefs, values, worldviews and associated inner (cognitive, emotional, relational) capacities [8–10], something that has also been highlighted in the recent reports of the International Panel on Climate Change [11,12]. This type of transformation involves exploring the role of the internal dimensions of human life, and the links between climate change and society. It includes connections with other pressing societal crises, such as health inequalities, and other forms of injustice [6,13,14]. Accordingly, scholars have increasingly pointed out that only focusing on direct drivers, or so-called ‘shallow’ leverage points (e.g., technological innovations) rather than indirect, or so-called ‘deep’ leverage points (mindsets, values, norms), to reach mitigation targets could not only hinder progress, but even have negative effects on sustainability goals, through overlooking important synergies [5].

In this emerging rationale, climate change and other societal challenges can be partly understood as manifestations of our internal mental states: we enact our inner mindsets, value systems, beliefs, and worldviews [10,15,16]. The substantial role that internal dimensions play in shaping social life is supported by several theories, notably systems theory [17–19], integral theory [20], the three spheres of transformation framework [21], Theory U [22], and the internal–external transformation model [10]). They relate to behaviour change theories and social models of behaviour change that bring together struc- tural and individual factors e.g., social practice theory [23–25] and sustainable transition management [26,27] but promote a more relational understanding of sustainability transformation [28,29]. Particularly, they depict the potential of all individuals as agents of change for sustainability across individual, collective, and system levels (ibid). This article focused on the so-called inner sphere of transformation (related to internal individual and collective change and its influence on sustainability across scales), which means that the entry point is not on the practical or political spheres of transformation (i.e., behavioural change and systems change).

Emerging concepts and terms, such as ecoanxiety, ecological grief, solastalgia, and biospheric concern are another indication of the growing interest and research into the internal implications of external events, and vice versa [30–34]. Experiencing extreme events first-hand, or through feelings of uncertainty and various forms of media can, for instance, have short-term and indirect long-term health implications that impair our capacities to act at an individual and societal level, and which further increase climate risk [31,35]. Transformative efforts are thus needed to safeguard both individual and planetary health and wellbeing.

Although the links between internal and external system change for sustainability are receiving increased attention, there are important knowledge gaps concerning the underlying dynamics and processes that are essential for inner change, and how these translate into impactful action across scales [6,10,13,36–38]). More empirical research is needed to understand how certain internal human dimensions, or states, accelerate transformation towards sustainability (see e.g., Refs. [8,10,13].

Accordingly, scholars are now more and more often challenging sustainability education and the competencies that are needed, as they have so far mainly been discussed from a cognitive perspective and disembodied and detached from emotions, arguing for the neglected but important role of inner dimensions in sustainability work [13,39–42]. Various competency frameworks have recently emerged to support sustainable development, but it is only recently that they have also recognised the importance of inner capacities, and related empirical work is vastly lacking [43,44]. Educational settings still impose the risk of hampering transformative learning due to their ontological and epistemological traditions, where ideas of compartmentalisation and reductionism fail to capture the complexity and interconnection of sustainability issues [13]. As a response, courses and educational programs are offered with aims to offer a more holistic and relational worldview with different modes of knowledge [28,29,38] that also tap into the learner’s inner perspectives and bridge the gap between theory and practice [39,40]. For instance, UNESCO has recognised the importance of education that goes beyond transferring scientific information concerning environmental issues and that includes interdisciplinary pedagogy that empowers learners and enables self-direction in the learning process [45].

Our study addresses a research gap as it aims to analyse inner–outer change processes at individual and group levels that have the potential, in turn, to support or catalyse systemic engagement for sustainability. We examined the adult education program called One Year in Transition (1YT), an international program situated in Sweden. This course was chosen because of its declared aim to address sustainable transformation by linking inner and outer dimensions, and by combining solutions at individual, collective and system levels. The program consists of four modules, spread out over a year, which introduce concepts that include sustainability, inner transformation and transition, permaculture, integral theory, and Theory U.

It combines study visits, online lectures, peer support groups and mentoring, as well as contemplative practices [22,46]. The program starts with building trust, providing an overview of current sustainability problems, and introducing the concept of inner transition and transformation [8,9]. The course literature includes Joanna Macys “The work that reconnects”, to deepen the understanding of what she has named the “Great turning” [46], which involves the emergence of new and creative individual and collective human responses. A related contemplative practice is the 4.6 km “Deep Time Walk”, where every meter represents a million years of planetary time.

A core feature of the program is open dialogues between participants on the possible future and paradigm shift. In addition, participants are expected to develop and run their own sustainability projects within a specific context and/or local community. More information on the One Year in Transition course is available inSwedish (since publication link is broken). The course took its inspiration from the Transition Network (accessed on 10 January 2023).

Methodology

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Data Analysis

We examined participants’ narratives with thematic analysis, which takes a first-person perspective when interpreting narrative data. This interpretative approach helps to identify and analyse pattens and themes in the data. It goes beyond a semantic analysis, as it identifies underlying patterns and assumptions that shape the semantic content found in the data [53,55].

Consistent with Braun and Clarke [53], and Nowell and colleagues [54], we adopted the following six-step approach found in thematic analysis: (1) familiarisation with the data; (2) generating initial ideas and themes through open coding; (3) interpreting and systematically categorising the content of interview transcripts into themes and associated patterns; (4) reviewing; and (5) further defining through axial and selective coding. The aim of the final step was to produce descriptions from themes. It is important to highlight that these steps are part of a circular (and not a linear) process as the analysis moves forward and backward across the data.

Two researchers, who were not present during the interviews, initially analysed the material independently. Interpretations were discussed between the two researchers after initial familiarisation and coding. By examining keywords and the linkages between them, distinct categories were identified that led to the identification of overarching themes. Whilst agreement and data saturation were achieved, this was not the main aim, but rather, to familiarise further with the data and explore other interpretations of the data and assumptions made by the coders. Identified themes were also presented and discussed with all the study’s researchers with the same aim. Themes were identified using an inductive approach rather than pre-existing theoretical frameworks and were the endpoint of the analytical process, found in the intersection of the dataset and researchers’ understanding and interpretation.

Results

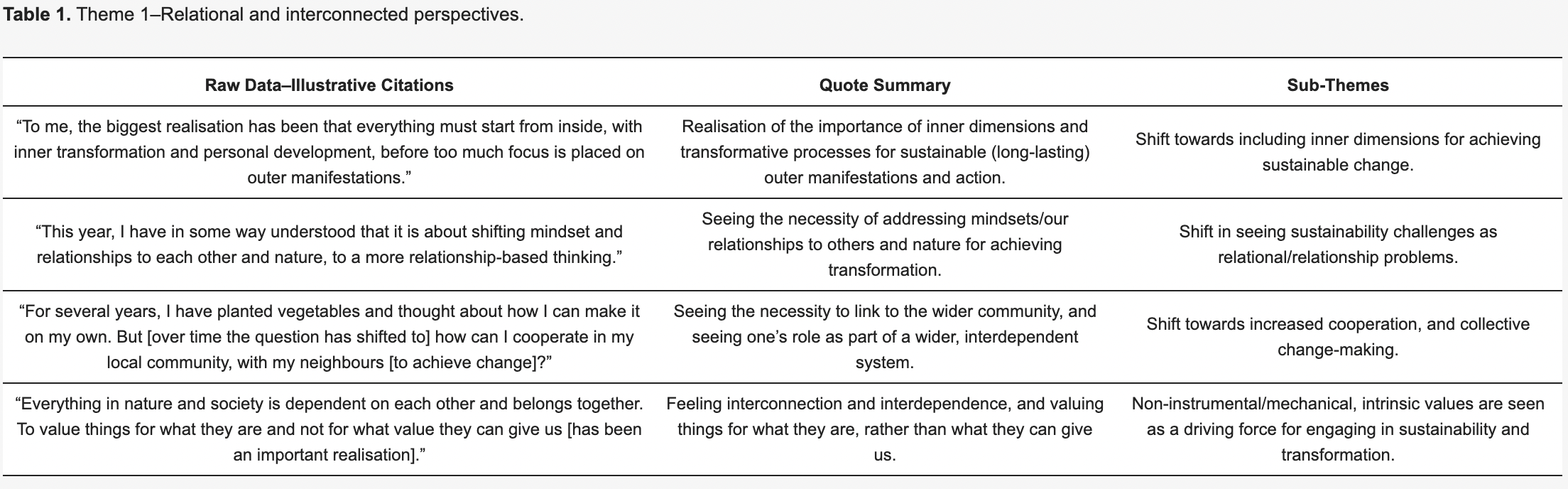

3.1. Relational and Interconnected Perspectives

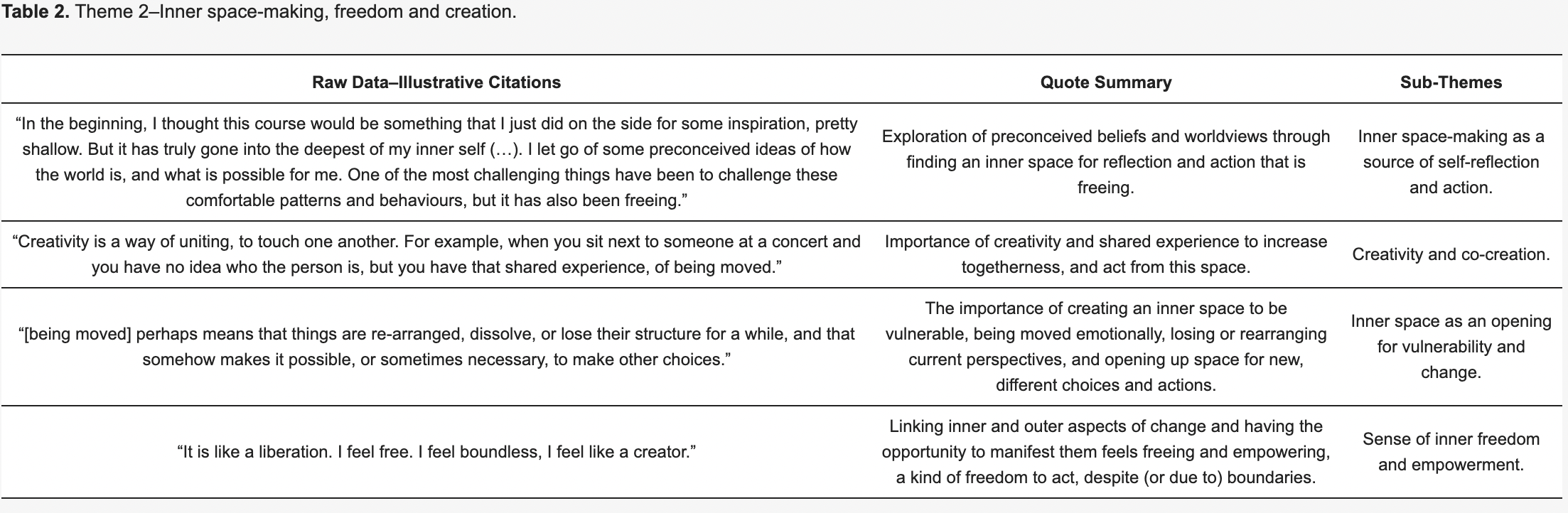

3.2. Inner Space-Making, Freedom and Creation

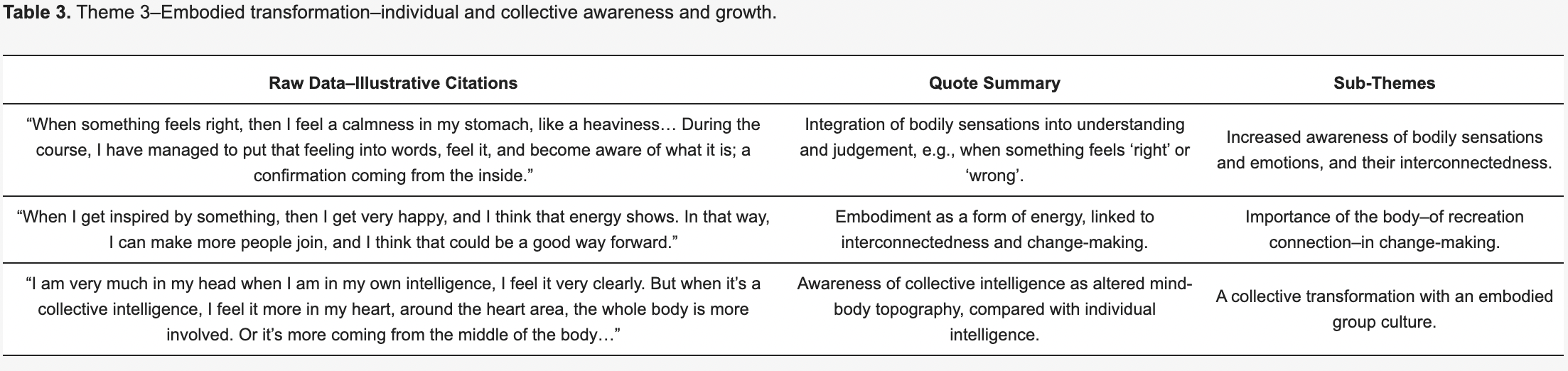

3.3. Embodied Transformation–Individual and Collective Awareness and Growth

The third theme relates to changes in perspectives that manifested over time, in an increasing (sense of) embodiment of inner–outer change.

Participants expressed an evolving understanding of inner processes and bodily sensations and connected this understanding to inner transformation and outer change-making. Moreover, they described the importance of being “in the whole body” with one’s “whole energy” and being able to identify and relate better to their own biases and reactions (e.g., emotions, fears, and other triggers). Being in one’s body was seen as an important aspect of knowing, along with being able to express oneself with one’s whole being, being authentic, and, thus, inspiring others.

3.4. Lived Embodiment–Change as Being–Being Change

The final theme relates to the embodiment of inner–outer change, where actions can be seen as a manifestation of change as being. It is related to the previous theme but has a stronger orientation toward (embodied) action. (The theories concerning embodiment refer to the role of the body in making sense of our thoughts and feelings, meaning that our bodily awareness has an impact on our cognition; how we understand ourselves as well as the world around us (see e.g., Refs. [65,66,67]).)

A clear expression of this process of change as being was the statement that “life has become the course.” Transformation was not merely seen as taking in information, but about creating space and opportunities for self-reflection, and tapping into one’s inner being (see Section 3.1, Section 3.2 and Section 3.3). This supported lived and embodied experiences, and catalysed action through creating personal insights, and strengthening an inner compass (see Section 3.2).

Discussion

Participants described a reciprocal relationship between individual and collective transformation, as well as between inner and outer processes, which is in line with increasing calls for more relational approaches to sustainability [28,29,68,69,70,71,72]. Accordingly, our findings are in line with, and illustrate, in granular empirical detail, theoretical notions of sustainable transformation and associated leverage points [17,18].

In addition, the inner aspects that we have identified as crucial for transformation support recent knowledge development and theory on transformative capacities or so-called inner development goals [73]. These capacities can be grouped into five clusters: awareness, connection, insight, purpose, and agency [10,37], which are all reflected in the identified themes (see Section 3.1, Section 3.2, Section 3.3 and Section 3.4). In addition, our analyses of the empirical data illustrate how the necessary capacities interrelate and translate into internal and external change. Insight is, for instance, visible in participants’ changed use of language, which becomes non-dualistic and multi-layered, and their increased focus on relations, perspective-taking, and the integration of different types of knowledge. This was, in turn, closely related to changes in self-awareness, a realisation of one’s potential influence and, ultimately, one’s intrinsic motivation or purpose.

Connection was one of the most dominant factors. It is linked to, and has implications for, all the themes and associated capacities identified in our data. Feelings of connection to self, others, and the environment were strongly related to reflections and insight on purpose, in other words, the activation and reflectivity of one’s values, intentions and responsibility led to an increasing circle of identity, care, and responsibility (see Table 1). The importance of connection has been underscored in sustainability (see Ref. [10]), leadership development [74] and theories concerning education and adult development [75]. The interviews highlighted an intrinsic value orientation. Inner and outer processes, along with living beings and natural systems, were ascribed internal value, rather than just being valued for their function (see also the theory of mind described in Frith and Frith [76]). The perceived oneness of life was not necessarily seen as a unification, but rather as tuning in to the individual’s surroundings (portrayed as, for example, “wave motions around bodies of relation”) as a source of action-taking. Previous research has for instance found a sense of connection and relatedness to nature to predict pro-environmental behaviours [77], whereas social identification and connection to animals has been linked to a greater desire to help animals in an altruistic and empowering way [78].

Many participants described increased awareness. They highlighted how they had experienced increased presence, attention, and emotional processing that had enabled increased psychological and cognitive flexibility. Awareness also relates to strengthening capacities to listen and communicate and being open to change [10]. This is confirmed by our study, where participants stated that they had developed a toolbox that helped them to speak about, and understand their own reactions, emotions, and impressions. The provision of a space where they could be vulnerable and safe, and visualise and practise the manifestation of inner–outer transformation, enabled them to continue ‘listening inwards’, to be moved, to engage, and consequently to rearrange, dissolve or restructure their inner and outer lives (see Table 2 and Table 3). In addition, in line with an increasing recognition that creativity has an important role in tackling sustainability issues across sectors at multiple levels [79,80,81,82], participants saw creativity as an enabler for co-creation, and empowerment to transform in a way that moves beyond the status quo.

Importantly, being able to practise agency supported participants’ sense of empowerment and inner capacities that enhanced collaboration. Creativity played an important role in the experience of feeling free from certain limitations, and the joy of being an active (co-)creator of change (see Table 2). As illustrated by all four themes, transformation was achieved by enabling participants to tap into their inner potential, interests, and abilities. This finding is supported by previous studies, which have found that a culture of creativity and learning empowers individuals to take action to materialise their inner vision and values [79,83]. Participants described their transformation narrative and experience in relation to different timeframes, reflecting specific moments, or shorter or longer periods of time where transformation and associated inner capacities evolved or emerged. For some, certain life-changing events that had occurred before the course had forced them to think about changing their path. A phenomenon that has been described in individuals with, for example, exhaustion/burnout symptoms [84]. At the same time, all participants were open to the idea of transformation and, thus, were interested in taking the course in the first place. Our analyses show that the group engaged in a collective experience which developed throughout the course, and that is interrelated with, but differs from each individual’s experience over time. Independent of time or context, our analyses illustrate the role of self, both as a way to prompt inner reflection, and as a potential entry point for interventions to spur collective change, as indicated by previous research [13,85].

Furthermore, our analyses show that the transformation of our inner selves to support sustainability entails being able to deal with deeply embodied emotions; this poses a significant challenge and relates to all five clusters of transformative capacities [10]. As with any change, transformation is closely related to individual and societal resilience, or the ability to utilise inner strengths and outer resources [86]. In this study, many participants explicitly acknowledged the importance of emotions and emotional processing for change, decision-making, and action. Using emotions as a tool, and discomfort as a guide were particularly emphasised (see Section 3.4). As the course progressed, participants developed a deeper understanding of their inner feelings and processes in relation to their surroundings, and how to act accordingly. This outcome resonates with studies suggesting a link between mindfulness and sustainable climate adaptation and non-fatalistic attitudes [87,88], as well as current theories regarding embodiment, where all experiences are, ultimately, embodied, and knowledge is accessed through the senses [66,67]. Current theories on learning show that emotions, bodily sensations, and cognition are intertwined, and underlying motivations and intentions are crucial [89].

In addition, the idea of not shying away from discomfort but rather placing it at the centre of transformation united several themes (see Section 3.2 especially regarding vulnerability, Section 3.3 on bodily sensations/triggers and Section 3.4 on embodiment). The role of discomfort was present in participants’ language and was closely tied to notions of creativity and change-making. By identifying the role of different kinds of discomfort, as well as accepting discomfort during change, participants developed the ability to differentiate between when to move away from discomfort or move towards/stay in it to support individual, group, and societal sustainability. Using terminology from relational frame theory, this can be interpreted as an improvement in participants’ psychological flexibility during the course, suggesting that psychological flexibility is an important mechanism of change [90,91]. This observation is also in line with studies that show that experiential avoidance, and associated cognitive entanglement are key features in psychological inflexibility. The latter can be seen as the cause of both resistance to needed transformation, and psychological suffering [56]. It can thus be hypothesised that this understanding has translated into an acceptance amongst participants, despite its impact on the individual’s sense of discomfort.

Creating safe spaces that allow participants to engage in feelings of discomfort and reflexivity seem to be critical in setting the context for challenging individual and collective paradigms that underlie sustainability challenges [37]. There is also the suggestion of how transformative pedagogy can make use of discomfort, criticality, and uncertainty in teaching and thereby create “brave spaces” (see Refs [91,92]). Moreover, blaming others and common us-versus-them dynamics only seem to perpetuate unsustainable systems instead of exploring underlying feelings of anxiety, greed or guilt [28,29,93,94]. In line with this, other studies increasingly highlight that ecological crises such as climate change originate in our ‘blindness’ as to how they relate to our individual and collective exploitative mindsets [16,58]. This blindness stems from failing to take into account the fact that human awareness is not only partial and biased, but also results in inadequate climate responses and conditions in which we are exhausted and are exhausting the Earth [16]. To regain contact with our real experience, scholars thus increasingly argue that we must end the transformation of all aspects of our lives into an object of consumption, whilst developing the courage to change our society across individual, collective and system levels [10,58]. Participants echoed this observation, for instance pointing out how they had started treating themselves more as humans rather than machines, with a focus on finding a balance between engagement and rest, which they linked to concepts of de-growth and societal sustainability.

Overall, our analyses show that the 1YT program catalysed inner individual processes and had an influence that goes beyond individual lifestyle changes. Through strengthening psychological and cognitive flexibility, emotional regulation, and establishing the conditions and processes for creativity and trust to link inner and outer transformation, sustainability became an embodied way to save energy and regenerate at personal, group, and societal levels. The combination of tools and practices decreased feelings of overwhelm, apathy, anxiety, and fear. Together with the creation of an environment of learning, where mistakes were invited and non-stigmatized, the threshold for action-taking was lowered. Our study thus contributes to the growing field of education for sustainability and associated calls for more relational and integral approaches and pedagogies that support inner–outer change [5,13,28,37,38,45,57,60,95,96,97].

Conclusions and Future Directions

Our study shows that transformation is a multi-layered, complex process where inner and outer processes develop simultaneously, and interact. It also involves change to our inner dimensions, behaviours, cultures, and systems. The role of education in transformation lies, in this context, not only in terms of knowledge development, but also in its potential to create and hold spaces in which individuals can experience, reflect, and begin to embody personal insights. This helps to relax our dominant individual and societal beliefs, and worldviews, and develop the inner capacities and space from which to take action. Nourishing capacities and intrinsic values ultimately offer greater promise for practice, by manifesting this change in mindsets, values, and norms both individually and collectively. Furthermore, engagement in such experiences leads to the creation of communities of practice, which may also help to deal with the discomfort of “staying in the trouble”, and bolster courage to continue embodying these practices outside of one’s direct circle. Methodologically, our study shows that micro-phenomenology can help shed light on how spaces of inner transformation are emerging and translate into outer change. Micro-phenomenology methodology helps guiding participants towards deeper reflections, associated emotions and thoughts, whilst also the interviewer accounts become more in-depth.

First, we need to better-understand how to integrate different disciplines and methods, in order to nourish inner–outer change at individual and collective levels. It would, for instance, be valuable to integrate the study of positive personality change, and the known stages of personal development, in order to identify periods that offer greatest receptivity to change. This insight would feed into pedagogical design in sustainability educational settings [10,100]. Accompanying this, we need to increase our understanding of which methods and processes can best-tap into inner experiences, including subtle changes and tipping points that translate into the likelihood of action [37,57,58,101,102,103].

Such findings would inform the (re-)design of existing educational programs or sustainability courses within curriculums and recommend appropriate adjustments. These changes could include accessibility, modes of learning, and methods that promote a greater sense of interconnection and belonging. Importantly, longitudinal studies are needed to explore the effects of educational efforts that address inner dimensions. This may involve tracking participants’ connectedness and attitudes to nature, people, and animals over time, as well as their willingness to make personal sacrifices and trade-offs to the benefit of, for example, ecosystem health, social justice and equity, and animal rights and welfare [104].

Second, we need to better-understand the integration of knowledge systems and the decolonization of education. Going forward, our research and actions should be informed by the knowledge of indigenous groups about environmental sustainability that has existed, but remained marginalised, for hundreds of years, and is intrinsically linked with the identified themes of inner–outer change [10]. In addition, the rights and interests of these groups must be brought to the fore.

Thirdly, future research could explore the role of narratives and new imaginaries for inner–outer change. For example, it would be relevant to look further into the relationship between change in narrative identity and adversity, and the educational setting, or links between change in narrative identity and manifested behaviours towards transformation for sustainability [105,106,107,108].

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interest to declare.

References

- O’Grady, C. Time grows short to curb warming, report warns. Science 2021, 373, 723–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson-Delmotte, V.; Zhai, P.; Pirani, A.; Connors, S.; Péan, C.; Berger, S.; Caud, N.; Chen, Y.; Goldfarb, L.; Gomis, M.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC: Summary for Policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyper, J.; Schroeder, H.; Linnér, B.O. The evolution of the UNFCCC. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2018, 43, 343–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. Planetary boundaries: Exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.; Boyd, D.R.; Gould, R.K.; Jetzkowitz, J.; Liu, J.; Muraca, B.; Naidoo, R.; Olmsted, P.; Satterfield, T.; Selomane, O.; et al. Levers and leverage points for pathways to sustainability. People Nat. 2020, 2, 693–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; O’Brien, K. Climate and Society: Transforming the Future; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Volume 25, pp. 202–204. [Google Scholar]

- Robèrt, K.H. Tools and concepts for sustainable development, how do they relate to a general framework for sustainable development, and to each other? J. Clean. Prod. 2000, 8, 243–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ives, C.D.; Freeth, R.; Fischer, J. Inside-out sustainability: The neglect of inner worlds. Ambio 2020, 49, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horlings, L.G. The inner dimension of sustainability: Personal and cultural values. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 14, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C.; Osberg, G.; Osika, W.; Hendersson, H.; Mundaca, L. Linking internal and external transformation for sustainability and climate action: Towards a new research and policy agenda. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2021, 71, 102373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pörtner, H.-O.; Roberts, D.; Tignor, M.; Poloczanska, E.; Mintenbeck, K.; Alegría, A.; Craig, M.; Langsdorf, S.; Löschke, S.; Möller, V.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC Climate Change: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shukla, P.R.; Skea, J.; Slade, R.; Al Khourdajie, A.; van Diemen, R.; McCollum, D.; Pathak, M.; Some, S.; Vyas, P.; Fradera, R.; et al. (Eds.) IPCC Climate Change: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Woiwode, C.; Schäpke, N.; Bina, O.; Veciana, S.; Kunze, I.; Parodi, O.; Petra Schweizer-Ries, P.; Wamsler, C. Inner transformation to sustainability as a deep leverage point: Fostering new avenues for change through dialogue and reflection. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 841–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, W.N.; Barnett, J.; Brown, K.; Marshall, N.; O’Brien, K. Cultural dimensions of climate change impacts and adaptation. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2013, 3, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueres, C.; Rivett-Carnac, T. The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis; Reed Business Information: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wamsler, C.; Bristow, J. At the intersection of mind and climate change: Integrating inner dimensions of climate change into policymaking and practice. Clim. Chang. 2022, 173, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meadows, D.H. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System; The Sustainability Institute: Tamworth, NH, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H. Thinking in Systems: A Primer; Chelsea Green Publishing: Chelsea, VS, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Capra, F.; Luisi, P.L. The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, K. A Brief History of Everything; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, K.; Sygna, L. Responding to climate change: The three spheres of transformation. In Proceedings of the Transformation in a Changing Climate, Oslo, Norway, 19–21 June 2013; University of Oslo: Oslo, Norway; pp. 16–23, ISBN 978-82-570-2000-2. [Google Scholar]

- Scharmer, O. The Essentials of Theory U: Core Principles and Applications; Berrett-Koehler Publishers: Oakland, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Reckwitz, A. Toward a theory of social practices: A development in culturalist theorizing. Eur. J. Soc. Theory 2002, 5, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E. Beyond the ABC: Climate change policy and theories of social change. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hargreaves, T. Practicing behaviour change: Applying social practice theory to pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Kemp, R.; van Asselt, M. More evolution than revolution: Transition management in public policy. Foresight 2001, 3, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbong, G.; Loorbach, D. (Eds.) Governing the Energy Transition: Reality, Illusion or Necessity? Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, Z.; Böhme, J.; Lavelle, B.D.; Wamsler, C. Transformative education: Towards a relational, justice-oriented approach to sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 1587–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, Z.; Böhme, J.; Wamsler, C. Towards a relational paradigm in sustainability research, practice and education. Ambio 2020, 50, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cianconi, P.; Betrò, S.; Janiri, L. The impact of climate change on mental health: A systematic descriptive review. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C.; Krygsman, K.; Speiser, M. Mental Health and Our Changing Climate: Impacts, Implications, and Guidance; American Psychological Association and ecoAmerica: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton, S.; Manning, C. (Eds.) Psychology and Climate Change: Human Perceptions, Impacts, and Responses; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Norgaard, K.M. Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions, and Everyday Life; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ojala, M.; Cunsolo, A.; Ogunbode, C.A.; Middleton, J. Anxiety, Worry, and Grief in a Time of Environmental and Climate Crisis: A Narrative Review. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 35–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N.R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2018, 8, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, P.W. The philosophy of theory U: A critical examination. Philos. Manag. 2019, 18, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wamsler, C.; Schäpke, N.; Fraude, C.; Stasiak, D.; Bruhn, T.; Lawrence, M.; Mundaca, L. Enabling new mindsets and transformative skills for negotiating and activating climate action: Lessons from UNFCCC conferences of the parties. Environ. Sci Policy 2020, 112, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wamsler, C. Education for sustainability: Fostering a more conscious society and transformation towards sustainability. Int. J.Sustain. High. 2020, 21, 112–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parodi, O.; Tamm, K. (Eds.) Personal Sustainability: Exploring the Far Side of Sustainable Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, G.G. Making sustainability personal: An experiential semester-long project to enhance students’ understanding of sustainability. Manag. Teach. Rev. 2021, 6, 7–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojner Horwitz, E.; Thyrén, D. Developing a sustainable and healthy working life with the arts: The HeArtS program—A research dialogue with creative students. Creat. Educ. 2022, 13, 1667–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, E.; Rimanoczy, I. (Eds.) Revolutionizing Sustainability Education: Stories and Tools of Mindset Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Brundiers, K.; Barth, M.; Cebrián, G.; Cohen, M.; Diaz, L.; Doucette-Remington, S.; Zint, M. Key competencies in sustainability in higher education—Toward an agreed-upon reference framework. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giangrande, N.; White, R.M.; East, M.; Jackson, R.; Clarke, T.; Saloff Coste, M.; Penha-Lopes, G. A competency framework to assess and activate education for sustainable development: Addressing the UN sustainable development goals 4.7 challenge. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howell, R.A. Engaging students in education for sustainable development: The benefits of active learning, reflective practices and flipped classroom pedagogies. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 325, 129318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macy, J. Stories of the Great Turning; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Vermersch, P. Introspection as practice. J. Conscious. Stud. 1999, 6, 17–42. [Google Scholar]

- Vermersch, P. Describing the practice of introspection. J. Conscious. Stud. 2009, 16, 20–57. [Google Scholar]

- Petitmengin, C. Describing one’s subjective experience in the second person: An interview method for the science of consciousness. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2006, 5, 229–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitmengin, C. Towards the source of thoughts: The gestural and transmodal dimension of lived experience. J. Conscious. Stud. 2007, 14, 54–82. [Google Scholar]

- Petitmengin, C.; Remillieux, A.; Valenzuela-Moguillansky, C. Discovering the structures of lived experience. Phenomenol. Cogn. Sci. 2019, 18, 691–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Thomas, I. Synthesising case-study research–ready for the next step? Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 751–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowell, L.S.; Norris, J.M.; White, D.E.; Moules, N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2017, 16, 1609406917733847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojner Horwitz, E.; Stenfors, C.; Osika, W. Contemplative Inquiry in Movement: Managing Writer’s Block in Academic Writing. Int. J. Transpers. Stud. 2013, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojner Horwitz, E.; Stenfors, C.; Osika, W. Writer’s Block Revisited: A Micro-Phenomenological Case Study on the Blocking Influence of an Internalized Voice. J. Conscious. Stud. 2018, 25, 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Petitmengin, C. Anchoring in lived experience as an act of resistance. Constr. Found. 2021, 16, 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. The Narrative Construal of Reality. In The Culture of Education; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 130–149. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, D. Narrative and the real world: An argument for continuity. Hist. Theory 1986, 25, 117–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, V. Life stories and shared experience. Soc. Sci. Med. 1997, 45, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Merwe, S.E.; Biggs, R.; Preiser, R.; Cunningham, C.; Snowden, D.J.; O’Brien, K.; Jenal, M.; Vosloo, M.; Blignaut, S.; Goh, Z. Making sense of complexity: Using sensemaker as a research tool. Systems 2019, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pöllänen, E.; Osika, W. Vi och” de andra”-social hållbarhet kopplat till hur vi känner, tänker och agerar i relation till andra djur. Soc. Med. Tidskr. 2018, 95, 132–140. [Google Scholar]

- Haila, Y. Beyond the nature-culture dualism. Biol. Philos. 2000, 15, 155–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A.; de Vignemont, F. Is social cognition embodied? Trends Cogn. Sci. 2009, 13, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immordino Yang, M.H.; Damasio, A. We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind Brain Educ. 2007, 1, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weibe, S.; Snowber, C. The visceral imagination: A fertile space for non-textual knowing. J. Curric. Theor. 2011, 27. Available online: https://journal.jctonline.org/index.php/jct/article/view/352 (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Räthzel, N.; Uzzell, D. Transformative environmental education: A collective rehearsal for reality. Environ. Educ. Res. 2009, 15, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Souza, D.T.; Wals, A.E.; Jacobi, P.R. Learning-based transformations towards sustainability: A relational approach based on Humberto Maturana and Paulo Freire. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 1605–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, S.; Haider, L.J.; Stålhammar, S.; Woroniecki, S. A relational turn for sustainability science? Relational thinking, leverage points and transformations. Ecosyst. People 2020, 16, 304–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitroff, S.J.; Kardan, O.; Necka, E.A.; Decety, J.; Berman, M.G.; Norman, G.J. Physiological dynamics of stress contagion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 6168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bojner Horwitz, E.; Harmat, L.; Osika, W.; Theorell, T. The Interplay between Chamber Musicians During Two Public Performances of the Same Piece: A Novel Methodology Using the Concept of “Flow”. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3677. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, T. Inner Development Goals: Background, Method and the IDG Framework; Report from the First Phase of the IDG Initiative. 2021. Available online: https://www.innerdevelopmentgoals.org/categories (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Kjellström, S.; Törnblom, O.; Stålne, K. A dialogue map of leader and leadership development methods: A communication tool. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7, 1717051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, T. Late Stages of Adult Development: One Linear Sequence or Several Parallel Branches? Integral Rev. 2018, 14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327513918_Late_Stages_of_Adult_Development_One_Linear_Sequence_or_Several_Parallel_Branches (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Frith, C.D.; Frith, U. Interacting minds—A biological basis. Science 1999, 286, 1692–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, wellbeing and pro-environmental behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiot, C.E.; Sukhanova, K.; Bastian, B. Social identification with animals: Unpacking our psychological connection with other animals. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2020, 118, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burroughs, J.; Dahl, D.W.; Moreau, P.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Gorn, G. Facilitating and Rewarding Creativity during New Product Development. J. Mark. 2011, 75, 53–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bentz, J.; do Carmo, L.; Schafenacker, N.; Schirok, J.; Corso, S.D. Creative, embodied practices, and the potentialities for sustainability transformations. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 17, 697–699. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, A.; Puente-Diaz, R. Creativity, innovation, sustainability: A conceptual model for future research efforts. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- d’Orville, H. The relationship between sustainability and creativity. Cadmus 2019, 4, 65–73. [Google Scholar]

- Bojner Horwitz, E.; Rehnqvist, K.; Osika, W.; Thyrén, D.; Åberg, L.; Kowalski, J.; Theorell, T. Embodied learning via a knowledge concert: An exploratory intervention study. Nord. J. Arts Cult. Health 2021, 1, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, G.; Perski, A.; Osika, W.; Savic, I. Stress-related exhaustion disorder–clinical manifestation of burnout? A review of assessment methods, sleep impairments, cognitive disturbances, and neuro-biological and physiological changes in clinical burnout. Scand. J. Psychol. 2015, 56, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, V.A.; Harris, J.A. The Human Capacity for Transformational Change: Harnessing the Collective Mind; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, S. Psychological and social aspects of resilience: A synthesis of risks and resources. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2003, 5, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamsler, C. Mind the gap: The role of mindfulness in adapting to increasing risk and climate change. Sustain. Sci. 2018, 13, 1121–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wamsler, C.; Brink, E. Mindsets for sustainability: Exploring the link between mindfulness and sustainable climate adaptation. Ecol. Econ. 2018, 151, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon-Singer, H.; Hendler, T.; Pessoa, L.; Shackman, J. The neurobiology of emotion—Cognition interactions: Fundamental questions and strategies for future research. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hayes, S.C. A relational control theory of stimulus equivalence. Dialogues Verbal Behav. 1991, 1. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313056812_A_relational_control_theory_of_stimulus_equivalence (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Ciarrochi, J.; Bilich, L.; Godsell, C. Psychological flexibility as a mechanism of change in acceptance and commitment therapy. In Assessing Mindfulness and Acceptance Processes in Clients: Illuminating the Theory and Practice of Change; New Harbinger Publication, Inc.: Oakland, CA, USA, 2010; pp. 51–75. [Google Scholar]

- Winks, L. Discomfort, Challenge and Brave Spaces in Higher Education. In Implementing Sustainability in the Curriculum of Universities; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Lundholm, C. Learning about environmental issues in engineering programmes: A case study of first-year civil engineering students’ contextualisation of an ecology course. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2004. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ801914 (accessed on 14 November 2021). [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Rieckmann, M. Academic staff development as a catalyst for curriculum change towards education for sustainable development: An output perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 26, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugher, J.E.; Osika, W.; Robert, K.H. Ecological consciousness, moral imagination, and the framework for strategic sustainable development. In Creative Social Change; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, D.W. Earth in Mind: On Education, Environment, and the Human Prospect; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sachs, J.D. The Age of Sustainable Development; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen, N.; Labonté, R. “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qual. Health. Res. 2020, 30, 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Game, E.T.; Tallis, H.; Olander, L.; Alexander, S.M.; Busch, J.; Cartwright, N.; Sutherland, W.J. Cross-discipline evidence principles for sustainability policy. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawickreme, E.; Infurna, F.J.; Alajak, K.; Blackie, L.E.; Chopik, W.J.; Chung, J.M.; Dorfman, A.; Fleeson, W.; Forgeard, M.J.C.; Zonneveld, R.; et al. Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. J. Pers. 2021, 89, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, J.; Werr, A. Sharing Errors Where Everyone Is Perfect—Culture, Emotional Dynamics, and Error Sharing in Two Consulting Firms. Acad. Manag. Discov. 2021, 4, 509–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Adm. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 350–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gallopín, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, H. Education, anthropocentrism, and interspecies sustainability: Confronting institutional anxieties in omnicidal times. Ethics Educ. 2021, 16, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bühler, L.J.; Weidmann, R.; Grob, A. The actor, agent, and author across the life span: Interrelations between personality traits, life goals, and life narratives in an age-heterogeneous sample. Eur. J. Pers. 2021, 35, 168–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendersson, H.; Wamsler, C. New stories for a more conscious, sustainable society: Claiming authorship of the climate story. Clim. Chang. 2020, 158, 345–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- von Wright, M. Narrative imagination and taking the perspective of others. Stud. Philos. Educ. 2002, 21, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Wright, M. Imagination and Education. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; 2021; Available online: https://oxfordre.com/education/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-1487;jsessionid=0218263782C459D2CD87D6B6E449E04D (accessed on 14 November 2021).

Copyright

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.